| tourism[s] | |||

| UP.DANIEL LUSTER | |||

|

|

[keywors] dislocation, movement, vision, romanticism, sublimnity, war, boundar, constructed image [background] Webster’s dictionary defines tourism as “the practice of traveling for recreation.” This definition begins to tell us something about the imbedded layers with in such a social construction as tourism. It is the desire to move, a fundamental part of human habitation of the world, coupled with an increased awareness of time and space brought with the modern period all set with in the frame work of the desire for entertainment [recreation]. It is essential to point out that tourism and travel are different operations, where traveling is the concerted effort to absorb, imbed and understand other places and cultures typically by spending large amounts of time in a place as well as learning the languages and the customs of a particular place. Tourism stands in contrast to this in that its primary concern is consumption and comfort in viewing of ‘meaningful’ places. “American tourism produces the authentic past with a fictive latitude in which literature, mythology and popular fantasy are blended together into the interpretation process called heritage. The tourist agrees to these flexible terms with no sense of loss.” The typical tourist yearns for the ‘authentic’ and ‘original’ while continually turning their head at the packaged and prescribed nature of the ‘tourist attractions’ that are designed for consumption of history as a commodity. [tourism + history] For the traveler time and space are of utmost consequence, laying the groundwork for every experience and creating the lense by which cultures are seen. It is a desire to place one’s self in the continuum of history, the real histories of a place both positive and negative. The tourist however either cannot or by nature of the touristic operation does not give consequence to time or space. Diller and Scofidio write that “By passing the limitations of chronological time and contiguous space, touristic time is reversible and touristic space is elastic. Consequently, correspondence between time and space – between histories and geographies – become negotiable.”[1] This then leads naturally to the creation, reproduction and eventually fabrication of ‘history’ in order to attract and keep the attention of the tourist. According to Diller and Scofidio the typical mantra of place for the tourist is “If a sight cannot be transplanted it can be replicated.”[1] It is the lack of interest in historiography that characterizes and denotes the landscapes of tourism. Travel is a reaction to home, to desire to leave and no longer be associated with a place or a people. This travel and subsequent displacement and dislocation, will then lead to homesickness and then to a desire to return home. The closed nature of this system is the fundamental basis for travel. “Tourism interrupts this circuit by eliminating the menace of the unfamiliar: that which produces homesickness. It domesticates the space of travel – the space between departure from home and return to it. The comfort of familiarity is the guarantee of chain hotels and restaurants.”[1] Interestingly enough, this desire for comfort in all areas is could be understood as one of the key factors in undermining our notions of home as it is. The blurring of what is and isn’t our world, what is and isn’t comfortable not only conflicts important aspects of public and private life but cheapens other cultures as well as the experience there of. [tourism + war] Tourism and war, it seems, intersect continuously in the news, but their association is not a recent phenomenon. Contemporary tourism evolved from heroic travel of the past, the roots of which are undoubtedly entangled with those of the earliest territorial conflict: after all, mobility has always been a key strategy of war. Soldiers were among the first travelers to penetrate and weaken territorial borders – not only through force, but through the dissemination of language and custom. Today, travel is no longer simply a provision of war: it has become a fringe benefit, even an incentive. [1] Tourism is an advent of the modern era, the diminishing size of the world due to modernization and speed of travel coupled with the publication of and preoccupation with history as a construct moved the activity of tourism into the realm of cultural obsession. In their book Back to the Front: Tourisms of War Diller and Scofidio expose the connections of tourismto essential notions of war and aggression. The massive displacement of people as well as the obsession with planning, maneuvering and tactics all speak of a wartime mentality and would dispel many of the assumed notions of tourism as the epitome of ‘peace time’. Both elicit the sublime as one of if not the chief experience of engagement in their framework, for the soldier by the very real possibility in death, for the tourist the construction of death in the context of a very ‘normal’ and familiar experience thus giving an even greater experience of the sublime to the onlooker who has distance at his disposal. One essential congruency between war and tourism is landscape or as Nicholas Saunders put it in his book Trench Art “for soldier and civilian alike, battlefields were (and remain) places where personal and cultural identities were explored and created.” [2] Following the First World War tourism of the war landscapes was a journey of remembrance of loved ones and of expectations of experience. Saunders writes, “Photographic images blended with imagination to produce a landscape of expectations in the pilgrim’s mind.” This then essentially causes the tourist to supper impose their own understandings up one the landscape, ‘so this is what its like to be in a battle,’ which give an interesting connection between real experience of a war and a touristic reconstitution of that same experience.

[references] 1. Back to the Front: Tourisms of War, ed. Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio (Basse-Normandie: F.R.A.C, 1994): 20-41. Marita Sturken, Tourists of History (London: Duke University Press, 2007) 2. Nicholas J. Saunders, Trench Art: Materialities and Memories of War (New York: Berg, 2003): 127, 144. Christine Macy and Sarah Bonnemaison, Architecture and Nature: Creating the American Landscape (New York: Routledge, 2003)

barriers | landscapes of war | postcard | tourisms | reasonable war | american myth |

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| 03 | |||

01. image of D-Day invasion, Normandy, France.

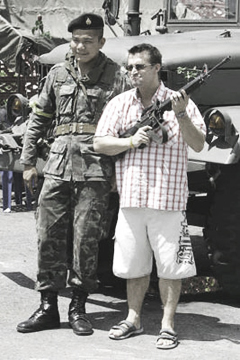

02. tourist with Indonisian soldier during violent military cope.

03. rollar-tourists in Paris, France. |

|||

| © university of tennessee college of architecture and design | |||